Although the Clarksville community, which was founded in 1871, was one of the first freedmen’s communities in Austin, it was certainly not the only one. Following emancipation, many freedmen and their families moved to frontier towns like Austin, which were somewhat less oppressive than other parts of the state, like East Texas.

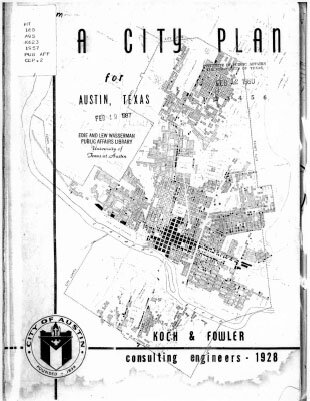

In 1870, the population of Austin was 36.5% Black, with people living in at least 15 identified freedmen’s communities across the city. These included Wheatville (near 24th Street and Rio Grande), Pleasant Hill and Mason Town (both east of Waller Creek between East 3rd and East 11th Streets), Robertson Hill (near the French Legation and east of Pleasant Hill), Gregory Town (East 7th Street to Rosewood between Chicon and Comal Streets), Southside (between South 1st and South 5th Streets from Monroe to Oltorf Streets), the Barton Springs area (between Goodrich and Kinney Avenue south to near Oltorf Street), and Kincheonville (southwest near Brodie and Davis Lanes).

While the social movement of Black people within Austin was prescribed by oppressive Jim Crow Laws, the residents of these communities had social, business, familial, and religious connection to the other neighborhoods that functioned as an interconnected network that sustained Black life and commerce in Austin.

In November 1917, the United States Supreme Court in Buchanan v Warley ruled that zoning laws that segregated by race were illegal. Still, the Anglo political leadership in Austin was interested in finding legal methods to enforce segregation of the races.

The “Austin City Plan of 1928” was adopted by the Austin City Council to address the “Negro Problem”. At the time, Austin’s city leaders claimed that providing “separate but equal” facilities and services in multiple communities across the city was too expensive.

As included in the Koch & Fowler consultants recommendation to the Austin City Council:

“There has been considerable talk in Austin, as well as other cities, in regard to the race segregation problem. This problem cannot be solved legally under any zoning law known to us at present. Practically all attempts of such have been proven unconstitutional.

In our studies in Austin we have found that the Negroes are present in small numbers, in practically all sections of the city, excepting the area just east of East Avenue and south of the City Cemetery. This area seems to be all Negro population. It is our recommendation that the nearest approach to the solution of the race segregation problem will be the recommendation of this district as a Negro district.

This will eliminate the necessity of duplication of white and black schools, white and black parks, and other duplicate facilities.”

The all-white, all-male, Austin City Council adopted the City Plan on March 22, 1928.

Enforcement of the City Plan included termination of city utilities in order to force Black residents to leave neighborhoods like Clarksville, and move east. The Plan also codified the segregation of Pease Park as “Whites Only”, with the city creating Rosewood Park in 1929 as the “Blacks Only” park.

While laws like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 have struck down forms of legal segregation, Austin’s culture of racism exists to the present day, now coupled with an additional layer of economic segregation. A 2015 study found that the Austin metropolitan area had the highest level of economic segregation among all 350 U.S. metropolitan areas.

Pease Park & Pease Park Conservancy

Pease Park is one of Austin’s 14 district parks. By definition, each district park is intended to serve the area within a two-mile radius. Pease Park Conservancy is committed to fulfilling the service area goals by developing and providing culturally competent programming desired by the communities the park serves. Organizationally, the Conservancy is working to be more reflective of these communities, and has created a mechanism to design and build a space of equity and belonging. If you are interested in joining us in these efforts, please contact us at info@peasepark.org

This is the third in a series to acknowledge and recognize Black History Month and the history of Pease Park and its surroundings.

Sources:

Austin History Center

Austin American-Statesman

City in a Garden, Andrew M. Busch

East End Cultural District

Segregated City, Florida & Mellander